EVs are moving away from lead-acid batteries, but this won't solve the ULAB recycling problem

As electric vehicles (EVs) reshape the automotive industry, a common assumption is that they'll eliminate lead-acid batteries, and potentially solve the environmental challenges of used lead-acid battery (ULAB) recycling.

This makes sense — after all, the largest single use for lead-acid batteries globally is starting the engines of gas-powered vehicles (often called SLI batteries, for “starting, lighting, and ignition”). Since EVs don’t have combustion engines to start, shouldn't their increasing popularity mean the end of lead-acid batteries and their recycling problems in low and middle-income countries (LMICs)?

The answer, perhaps surprisingly, is probably not. There are two key reasons for this:

Most electric vehicles sold today still use lead-acid batteries

SLI batteries represent less than half of global lead-acid battery demand, and other uses will likely remain strong, especially in LMICs

Let's examine each of these factors in detail.

The Current State of Lead-Acid Batteries in EVs

Most EVs still have lead-acid batteries

EVs have two batteries: a primary battery (usually lithium-based), which powers the motor and provides range, and a secondary battery, which powers the car’s “auxiliary” electronic systems (think things like door locks, interior lights, and windows).

In most EVs sold today, these secondary batteries are lead-acid. Manufacturers include these secondary batteries due to a combination of safety concerns, improved efficiency, and interoperability with existing electronic systems.

It’s easier and probably safer to have a smaller battery you use to power a bunch of these electronics in your EV than to try to find some way to wire everything back to the large (and high-voltage) primary battery. And since the predominant low-voltage car battery technology is lead-acid, most automakers have decided it’s easiest to continue to use a lead-acid battery to power these auxiliary systems.

Getting specific data on the share of EVs that use lead-acid batteries is difficult. If you Google it, you’ll get a set of answers that generically confirm that most EVs use lead-acid batteries:

“Your electric car or plug-in hybrid is propelled by a sophisticated lithium-ion battery, but you'll probably also find a lead-acid 12-volt battery in there somewhere.”

- Car and Driver (2022)“Most EVs on the road today still carry around a 12 V lead-acid battery for standby power”

- Power.com (2022)

However, these articles miss the meaningful shift around lead-acid batteries that’s happened in the EV market over the last couple of years.

Consider the best-selling EV models globally for 2023:

Two companies clearly dominate the global EV market: BYD and Tesla. Between them, they manufactured most of the best-selling EV models in 2023.

Estimates suggest BYD is the largest global EV manufacturer, with a global market share of 21.1%, while Tesla comes in second at 12.7%. Combined, this gives them a 33.8% share of the global market.

The remainder of the EV market consists of a longer tail of smaller Western and Chinese manufacturers.

The world’s largest EV makers—Tesla and BYD—have fully shifted away from lead-acid batteries

Tesla

Tesla was the first big EV manufacturer to do so, announcing in 2021 that they were phasing out lead-acid batteries.

The owner’s manuals for the Model Y and Model 3 both confirm that vehicles manufactured after 2021 use a lithium-ion, not lead-acid, battery.

Why did Tesla make this switch? Elon Musk said in a 2021 interview it was because the lithium-ion batteries they replaced them with have “way more capacity, and the calendar and cycle life match that of the main pack.”

BYD

In November 2023, BYD announced that they too were entirely switching away from lead-acid batteries. They chose to use a secondary lithium-iron phosphate battery, the same chemistry that powers their larger battery technology.

It is difficult to figure out exactly when this switch was rolled out, or if it applied to all vehicles. I also found the English-language sourcing a little sketchy.

Since I was in Beijing last week, I figured the easiest way to get this information would be to go to a BYD dealership and ask them about it.

The dealership confirmed that all new BYD cars—both fully-electric and hybrid—no longer used lead-acid batteries. They also opened the hood of a couple of their EV models and showed me these new lead-free batteries, which are noticeably smaller than the lead-acid ones that were previously used.

That both Tesla and BYD have eliminated lead-acid batteries suggests this is the direction the EV market as a whole is moving.

It also means it’s probably feasible for traditional gas-powered automakers to fully switch away from lead-acid batteries for SLI purposes as well. However, I suspect there’s some level of inertia which, when combined with the generally lower costs of lead-acid batteries, means they won’t jump to make this switch.

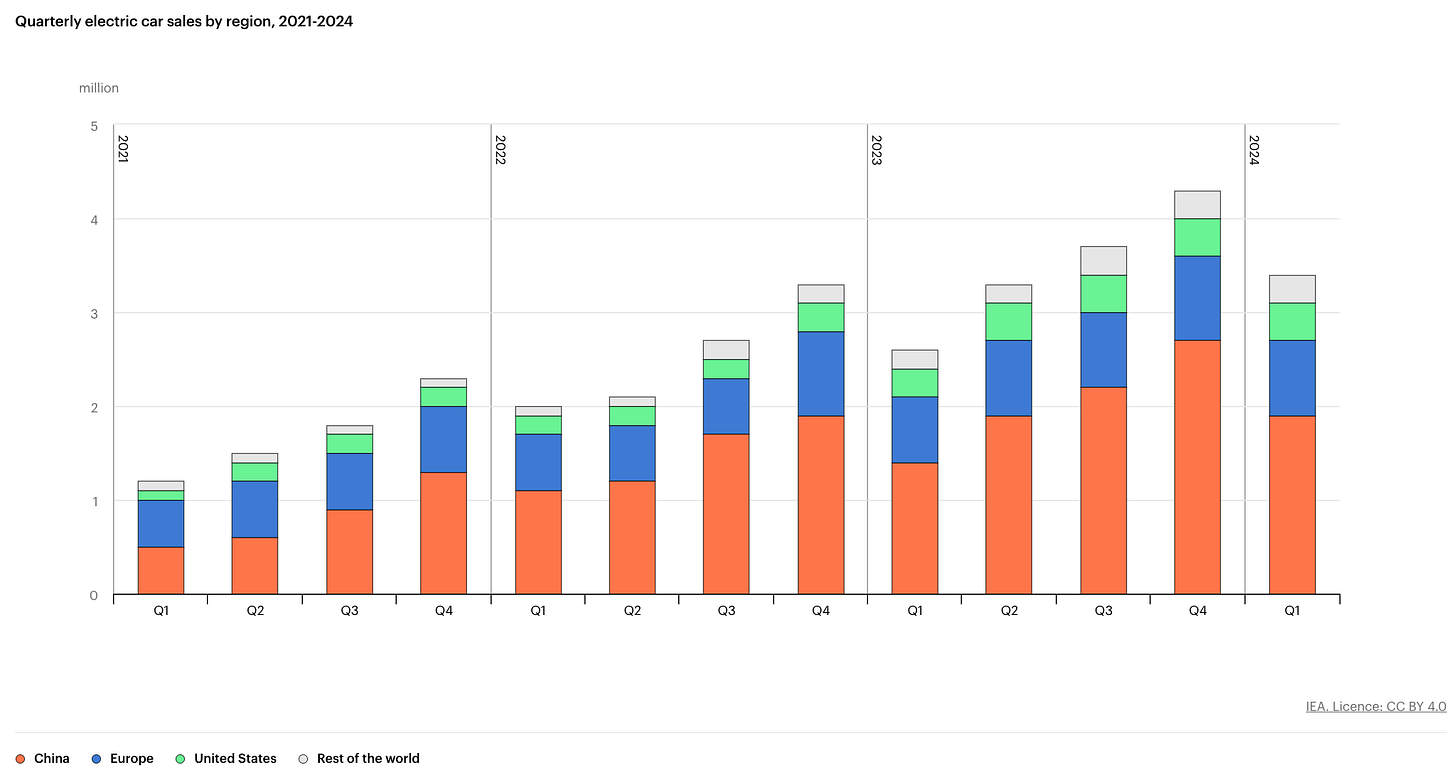

While this shift is probably good if you care about reducing lead poisoning from informal ULAB recycling, it will likely be a while before it has any significant effect. The vast majority of EVs still use lead-acid batteries—and EVs themselves only represented 18% of total car sales in 2023.

Automotive applications are less than half of the global lead-acid battery market

The shift away from lead-acid batteries in cars is also unlikely to address many of the core dynamics underlying low-standard ULAB recycling because most of the lead-acid battery market is for other applications.

Consider this data from the International Lead and Zinc Study Group (ILZSG):

While lead-acid batteries are heavy, large, and don’t last as long as some alternatives, they’re also relatively cheap.

Consequently, lead-acid batteries are very commonly used in stationary power supplies, which are used to store energy from solar panels, or provide backup power if the grid goes down. They’re also sometimes used as the primary power source in small electric vehicles (e.g., forklifts, golf carts, or e-bikes).

These non-automotive uses make up 55% of the market. This means that if the use of lead-acid batteries in all cars disappeared, you would still see a huge number of ULABs generated annually.

Further, growth in these non-SLI sectors may offset decreased usage in automotive applications, potentially diminishing or eliminating the overall reduction in lead-acid battery use.

Automotive uses are less prevalent in LMICs

LMICs are poorer, and as a result generally don’t have as many cars as richer countries. You can see this when you compare GDP per capita and cars per capita:

But what about other lead-acid battery uses?

Both stationary power supplies and smaller cheaper EVs are popular in many LMICs, and this trend seems likely to keep growing. Poorer countries are more likely to use off-grid solar and backup power supplies, and they’re more likely to buy cheaper (if inferior) lead-acid batteries to power their small vehicles instead of more expensive lithium ones.

If you look at where off-grid solar is likely to grow, it is also in poor countries that fail to provide reliable access to electricity:

Smaller electric vehicles, like e-bikes and e-rickshaws, seem to be a large source of ULABs in LMICs. In Bangladesh, for example, the International Lead Association (ILA) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) estimated that e-rickshaws were responsible for 70% (!) of all ULAB generation, followed by solar systems.

That these other lead-acid battery uses—solar panels and small electric vehicles—are so common in LMICs, where informal recycling is the largest problem, might mean that the EV transition away from lead-acid batteries will have a smaller effect on lead pollution than its share of the global market might suggest.

Right now, almost all new EVs are being sold in China, Europe, and the US. It is likely these places—which do not struggle with informal ULAB recycling—where a shift among EV manufacturers away from lead-acid batteries will be most impactful.