How Brazil Solved Its Lead-Acid Battery Problem

A model for effective battery recycling regulation

Updates

May 7th, 2024: Added details on INMETRO certification for new batteries and tax elimination on scrap ULABs.

August 10th, 2024: Added link to 2023 IBER report.

Informal used lead-acid battery (ULAB) recycling is often seen as a basically unsolved and insoluble problem — despite being a major cause of global lead poisoning.

But analysts do sometimes cite one success story in solving the informal ULAB recycling problems: Brazil. A commonly cited discussion of this is a one-page summary in a 2020 report on ULABs from the Global Battery Alliance and the World Economic Forum.

Through a series of innovative policies and regulations implemented between 2008 and 2019, Brazil has successfully transitioned to a formalized and environmentally responsible system for recycling used lead-acid batteries (ULABs).

At the heart of Brazil’s solution is a market-based approach that aligns the economic interests of formal battery manufacturers, importers, and distributors with the country’s recycling targets. By mandating that these companies buy back or collect and recycle a substantial percentage of the new batteries they sell, alongside eliminating taxes to make the formal sector more competitive, Brazil has created a robust reverse logistics system that incentivizes the entire supply chain to ensure ULABs remain in the formal sector.

Brazil’s success story offers an example of how market-driven policies, coupled with narrow but effective regulatory oversight and industry collaboration, can help eliminate informal lead-acid battery recycling.

* A quick note on sourcing: Many of the sources used for this article were available exclusively in Portuguese. We relied on a combination of DeepL for direct translation and Claude/ChatGPT for additional clarification. Where English versions are available, we’ve linked them, and where not, we’ve uploaded DeepL translations where possible.

What did Brazil do?

Between 2005 and 2019, Brazil passed a series of laws targeting ULAB recycling. This came alongside a broader push towards environmentally-friendly recycling with an emphasis on reverse logistics and what was essentially extended producer responsibility.

Eliminating taxes on scrap batteries

One reason the formal sector struggles to compete with the informal sector is that they have to pay taxes on scrap batteries.

If you want to encourage the formal sector to purchase and recycle ULABs, you need to make it as cheap as possible for them to do so, and a good way to do this is to exempt them from things like sales tax that their informal competitors don’t need to pay.

As part of their battery policy, Brazil eliminated taxes on scrap lead-acid batteries. The tax exemption on ULABs was outlined in 2005 in Convênio ICMS 27/05. (Convênios ICMS are rules that integrate tax legislation in Brazil.)

Legal obligations and reverse logistics

The first set of regulation was devoted to establishing legal requirements and mandating reverse logistics systems (where each stage of the supply chain returns ULABs to the previous one, from retailers through distributors to manufacturers). But they lacked specific targets or details about implementation or how the government would effectively report compliance.

The next set of laws, which began at a state level and were then expanded nationally, required that manufacturers and importers show that they had repurchased or collected and formally recycled ULABs equivalent to some large percentage of the new ones they sold.

Targeting manufacturers and importers is particularly effective because these are the part of the supply chain easiest to monitor and enforce regulation against. Manufacturers are generally large out of necessity (battery plants are expensive!) and importers have to declare their goods with customs. They both require specific environmental licenses to start operations.

In order to meet these takeback regulations, manufacturers turn to their existing supply chains to get them to supply ULABs (thus, “reverse logistics”). They go to their distributors and say “we need your scrap batteries” — and they have leverage to do this, more on that later — and their distributors then go to retailers and do the same.

Retailers return these scrap batteries to their distributors, who send them back to the manufacturers, who then deliver them to formal recyclers. The formal recyclers issue proof that the batteries have been recycled, and the manufacturers use this to satisfy their legal buyback obligations with the government.

Manufacturers meet their regulatory obligations, while distributors and retailers make their manufacturers happy alongside a small profit.

One of the reasons reverse logistics is effective is that it reduces transportation costs.

While it may not make economic sense for a manufacturer to send a truck to go pick-up scrap batteries, it’s much cheaper to load scrap batteries onto a truck that’s already dropped off some new ones for delivery, making it much cheaper than alternative battery collection methods.

IBER

Since 2016, Brazil’s ULAB reverse logistics process has been partially managed by IBER (Instituto Brasileiro de Energia Reciclável), a third-party “managing entity” that’s an intermediary between the Brazilian battery industry and the government. IBER signs agreements with federal and state environmental regulators, where in exchange for IBER ensuring its members’ compliance with the relevant regulations, its members are exempted from having to individually prove their compliance to the government every year.

You don’t have to join IBER — you can instead choose to prove that you’re compliant with the myriad of national, state, and municipal regulation — but most of the Brazilian lead-acid battery industry is in IBER.

Has it worked?

The policies seem to have been a real success. From the WEF report:

“Before the development of Brazil’s ULAB model, regulation, the majority of post-consumption LABs were improperly discarded and processed by illegal smelters, who possessed no license and had no legal authorization to perform such activity.”

(Consequences of A Mobile Future Report, p. 20)

And we do know how many ULABs are being formally recycled now — more than 75% of all batteries sold as of 2022. This represents a major improvement in the country’s battery recycling sector.

If we assume recycling was sub-50% as per the WEF report, Brazil’s policies have eliminated at least half of its informal sector.

Brazil doesn’t have national blood lead level surveys, but there also appears to have been broad concern in academic literature about ULAB recycling as a source of lead poisoning in Brazil since the early 2000s.1

How it happened: a policy timeline

This is a relatively short summary of the laws associated with Brazilian ULAB recycling regulation.

The important ones are flagged with (**).

If you want a much more detailed analysis of the laws and their effects with links and/or translations, see the footnotes section or click on a particular footnote to jump to that law.

**2005 Convênio ICMS 27/05: Created a tax exemption for used lead-acid batteries.

**2008 CONAMA Resolution No. 401: This was the first major piece of ULAB-specific regulation. Required battery manufacturers/importers to register and submit management plans, called for ULAB collection points at retail centers, made the recycling of collected batteries the manufacturer’s responsibility, banned ULAB landfilling/incineration.2

2008 Federal Decree No. 6.514: Created fines and enforcement mechanisms for a wide range of environmental violations at a national level.3

**2010 National Solid Waste Policy: Mandated reverse logistics systems for batteries and other products, created chain of responsibility for waste products from manufacturers to consumers.4

2011 CONAMA Resolution No. 436: Imposed restrictions on emissions from secondary lead smelters.5

**2012 INMETRO Ordinance No. 299: Required certification and reporting for all lead-acid batteries sold in Brazil, some of this reporting included details on sales, recycling, and environmental compliance as well third-party audits.6

**2012 IBAMA Instruction No. 8/2012: Required ULAB recyclers and transporters to register and report data around quantities sold, transported, and recycled to the government. Increased reporting requirements for manufacturers and importers.7

2013 IBAMA Instruction No. 1/2013: Tied ULAB regulation to hazardous waste reporting requirements.8

2015 São Paulo Resolution No. 45: Created reverse logistics requirements in the state for products including lead-acid batteries. Companies had to prove to the SP government that they were complaint with reverse logistics.9

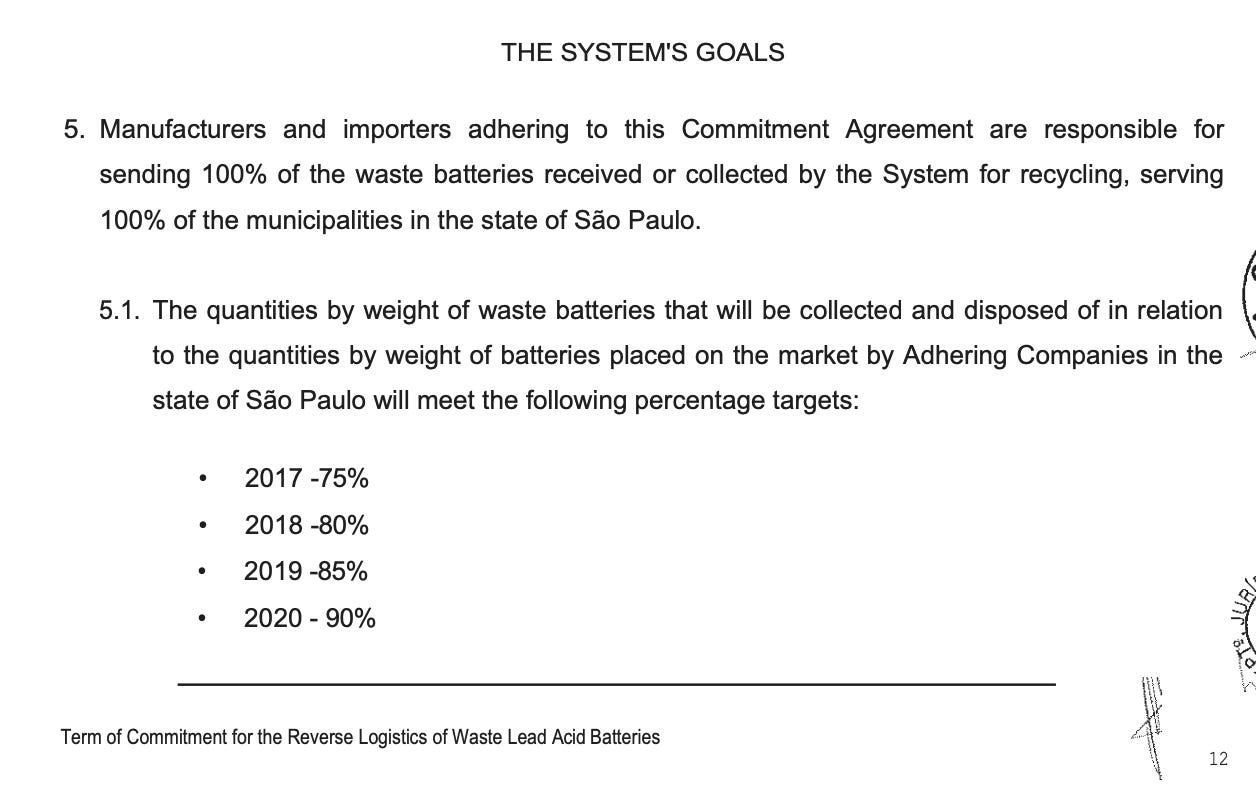

**2016 São Paulo Term of Commitment: The first important state-level terms of commitment, established IBER as the third-party managing entity and outlined specific battery buyback targets for manufacturers beginning at 75%.10

**2019 National Sectoral Agreement: This agreement, between the Brazilian battery industry and the Ministry of the Environment, expanded IBER's role nationally and set national targets.11

2023 Federal Decree No. 11.413: Formalized role of entities like IBER in certifying compliance.12

As you can see from this timeline, it took time for Brazil’s ULAB regulations to evolve to their current form. In particular, there was a lag between mandating reverse logistics and actually creating the infrastructure to enforce it — the introduction of IBER in 2016 came alongside specific targets for manufacturers.

Implementation

Up to around 2014/15, there was a strong set of national requirements for ULAB recycling, but no quantitative buyback requirements or details about implementation.

How well did the pre-IBER system work?

It’s a little hard to tell. I couldn’t find a quantitative analysis, but from case studies, it seems that by the early 2010s at least some reverse logistics processes were implemented.

A 2014 case study of a chain of auto centers in the state of Piauí which provides a look at some of these early reverse logistics efforts.

The company was a distributor for a major battery brand, and collected ULABs which they sold back to their manufacturer. All default pricing for batteries assumed the return of a used one — if customers fail to return batteries, they have to pay a higher ULAB-less price. (Under Brazilian law, customers are theoretically required to return their used batteries to retailers, but this is practically unenforceable.)

Per the authors, they broadly seemed to follow best practices around ULAB storage (obviously, selection bias here). The ULABs were collected and taken back to a central location using the same trucks that new batteries were delivered on.

The study highlights that although the laws were relatively strict, there was little regulatory enforcement at the distributor level. IBAMA, to whom much of the data was reported, was small and didn’t really conduct inspections. It portrays this as a flaw.

However, this dynamic is probably fine? The distributors participated because their manufacturers incentivized them to return their ULABs to them.

Indeed, it’s a strength of the policy design that Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment (MMA) doesn’t need to be inspecting random dealers, instead relying on manufacturers to ensure ULABs flow to the formal sector. It’s possible there are some problems with how downstream firms handle batteries, but compared to informal recycling and smelting, these are much better problems to have.

The creation of IBER

IBER was created in August 2016. It arose out of conversations with the MMA, and made its first state-level term of commitment (ToC) with the Brazilian battery industry and the State of São Paulo that year.13 (For details on earlier battery regulation in São Paulo, see the previous footnote.)

Terms of commitment are basically agreements allow the private sector to work with the government to figure out how they’ll comply with regulation. They’re usually signed between major industry groups and state environmental authorities.

(If you’re particularly curious about how these terms of commitment come together and how they work, this is a good English-language writeup focused on São Paulo.)

The 2016 São Paulo term of commitment

Under this term of commitment between the battery industry and Sao Paulo regulators, IBER — an independent non-profit — was to serve as the “managing entity” for the system.

It was responsible for helping its members comply with the the relevant ULAB regulation. Members pay a fee, splitting the costs of supporting IBER, and in exchange IBER coordinates compliance with the applicable regulations.

IBER’s largest responsibilities were (and are) to collect data on and ensure the compliance of its members. It would then report this data, which included information on new battery sales and the volume of ULABs collected, to CETESB annually. It worked closely with its individual members to help them structure their systems and collection to ensure they’re complying with relevant regulation.

It would also maintain a website with a list of its members and the locations of their ULAB collection points.

Membership in IBER was not required it exempted companies from needing to apply to CETESB for licensing. Further, IBER was required to notify CETESB of any companies that joined or left it, so the government would have a comprehensive list of the companies that had opted out of the centralized management system.

IBER expands

Over the next couple of years, IBER and the Brazilian battery industry would enter terms of commitment with several other states.14

A major expansion occurred with the signing of a national sectoral agreement in 2019. The sectoral agreement was similar to the state-level ToCs that preceded it, but extended ULAB buyback targets across the country and cemented IBER’s role as the managing entity for ULAB reverse logistics at a national level.

IBER quickly represented a large share of the Brazilian lead-acid battery manufacturers — by 2018, 75% of the lead-acid battery sales in Brazil were from companies represented by IBER (largely an effect of the economic concentration of a few states with ToCs like Sao Paulo), and it represents almost all major manufacturers and importers today.15

In 2023, Federal Decree No. 11.413/2023 provided more details for how management entities like IBER should manage member certification nationally, and required that they use independent auditors to help ensure members are compliant.

Finally, it required at a national level that all companies comply at a level equivalent to the reverse logistics targets that management entities did — this cemented management entities at the core of Brazil’s national ULAB policy, and meant that you could either join IBER, or prove you had met the same targets alone.

What IBER does

Most of what IBER actually does is collecting data from its members. Members submit monthly reports to IBER, which then aggregates, inspects, and reports the data. Because it receives data across the supply chain (from manufacturers through recyclers), it has real abilities to track and audit reverse logistics flows to ensure compliance.

IBER monitors this data to identify companies that are underperforming, and then works with them to help them meet regulatory standards. While most data is viewed and shared in aggregate, government agencies can access IBER’s data on a company-by-company level and access more detailed compliance reports.

On IBER’s online platform, companies can not only report data but also track their compliance with the applicable regulation and view statistics like their buyback percentage.

IBER issues certificates to its members to certify they’re in good standing, and anyone can verify these certificates on IBER’s website.

Once members are certified as being in good standing with IBER (meaning they’re reporting data accurately, complying with audits, and up-to-date on fees), they are exempt from many direct reporting and proof-of-compliance requirements across federal and state levels.

Starting in 2024, IBER will be cross-checking the numbers reported by members with the details of their tax invoices (Brazil has mandatory digital invoicing). This lets them further ensure that the numbers that companies are reporting to IBER are ultimately accurate — ULAB related fraud would have to align with tax fraud as well. They’ve built a digital system that allows them to take the invoices and obscure the invoices’ sensitive information like pricing, giving them just a view of the relevant details around battery weights sold/received.

Why IBER works

Economic incentives flow downstream from manufacturers

At its core, Brazil’s policies have been successful because of the way that they made battery manufacturers and importers ultimately responsible for reverse logistics.

Because they’re mandated to hit some buyback target, manufacturers/importers work with their downstream distributors to ensure that they are getting batteries back from those they’re selling batteries to — this is easier for them than going out and collecting the individual batteries themselves.

This 2022 paper (in English!) by Scur et. al. is the best analysis I’ve come across of the economics of this reverse logistics system. They conducted interviews with major manufacturers, recyclers, distributors, and retailers, and characterized the mechanisms by which Brazil’s reverse logistics work.

A lot of it relies on the substantial leverage that manufacturers have with their distributors. The biggest is that most major Brazilian battery manufacturers refuse to take orders for new batteries without a guarantee that the buyer will return an equivalent amount of scrap.

Manufacturers and importers also offer better pricing and payment terms to distributors who return more scrap. If they find a distributor is being non-compliant, they can put pressure on them by removing discounts or suspending sales — here, manufacturers, not regulators, are able to enforce compliance downstream.

Distributors are then incentivized to get ULABs from their retailers. And retailers are probably the group most easily able to get ULABs because they deal with people who are replacing their lead-acid batteries all day!

Consequently, retailers are encouraged to get consumers to return their batteries, which they do by adding additional fees if consumers do not trade in their old ones. (Customers seem happy to comply — that 2014 study of auto centers in Piaui found that 98% of customers turned in their old batteries.) For larger customers (think a bus company), the retailer will also go to the customer to pick up scrap.

They then send these batteries back to their distributors, who then sell them back to the manufacturers. Retailers and distributors are happy to participate because it’s profitable for them, and manufacturers get the scrap they need.

Finally, and this is part of why reverse logistics seems to work so well, it’s comparatively cheap. The old batteries are stored at each point of sale, and when a delivery of new batteries comes in, the old ones are taken back on the same truck to the distribution center.

The distributor can do the same to deliver scrap to the manufacturer, who can then make bulk deliveries to the recycler. This substantially reduces the transportation costs that would otherwise be associated with sending out a new truck to go pick up scrap at each stage.

Everyone seems to prefer a trusted third party

IBER serves a crucial role at the middle of Brazil’s ULAB reverse logistics system. But its role as a non-profit that coordinates between the government and industry seems to work particularly well.

Environmental regulators want reliable data on how well the battery program is going as well as which companies are and aren’t complying. There are strong laws mandating takeback rates and reverse logistics, but collecting and auditing this data at scale is annoying — they have a lot of things to regulate, of which batteries are one.

Regulators can effectively outsource this to IBER, who they trust to provide accurate data for its members and conduct audits, etc. In exchange for IBER providing accurate data and ensuring compliance, they let it certify its members and exempt them from certain kinds of environmental licensing requirements, including needing to prove compliance directly to the regulator.

Companies, and in particular battery manufacturers, want to comply with regulation. But they’d rather work with IBER, whose role is basically to help them comply, than manage state and federal environmental authorities directly.

In particular, IBER guarantees that by becoming a member, you’ll be compliant with all of the various federal, state, and municipal laws that might apply. Per IBER’s executive director Amanda Schneider in a 2022 speech to the Brazilian lead-acid battery industry, “we are also committed to ensuring that you have nothing to worry about with all these requirements and through a single system you are in compliance with all obligations.”

If you’re a company, it’s easier to work with IBER than the federal, state and local environmental authorities. It’s relatively small (a total headcount of 10 including two developers) and singularly focused on used lead-acid batteries. They seem to be very well run and relatively easy to work with. They’re also actively involved in negotiating and renewing terms of commitment and proactively managing relationships with regulators.

They provide what appears to be a very good digital platform for companies to report numbers and track compliance, with both a website and a mobile app. Having great software makes it easy to comply accurately, and the better the data they collect is, the more useful IBER is to everyone involved.

They audit members who report inconsistent data and work with a third-party auditor (as of right now, Apter) to ensure compliance.

At the most fundamental level, the technology is providing a ULAB compliance accounting tool — sort of like QuickBooks for batteries, if Intuit also reported data back to the government as you used it. It also provides some more complex features, including the ability to register details around transporters and automatically generate final disposal certificates.

How well has it worked?

The best way we have to assess the success of Brazil’s ULAB policies is through IBER’s data. I was able to find IBER’s annual reports for 2019, 2020, 2021, 2022, and 2023.16(English translations for each in the footnote.)

Among IBER’s members, collection rates are high. IBER as a whole collected 104% of their 312,064 tons of batteries sold in 2023, with rates ranging somewhat regionally from 102% of batteries sold in the Southeast to 89% in the North. (Interestingly, IBER didn’t have any terms of commitment in the North as of 2023 but has managed to be successful there nevertheless.)

IBER says that they represented 76% of all batteries sold in Brazil in 2023, and took back more batteries than they sold. If we compare this to WEF report’s description of pre-reverse logistics Brazil, where “the majority of post-consumption LABs were improperly discarded and processed by illegal smelters, who possessed no license and had no legal authorization to perform such activity,” this appears to be a real policy success.

Again, the WEF did not cite a source for that statistic, but regardless, Brazil went from not having a major system for ULAB management to more than 76% of batteries part of the system managed by IBER — if we include companies’ individual systems, this number is likely higher.

They’ve also seen rapid membership growth, and their members include the largest companies in the Brazilian battery industry.

However, IBER maintains that at least some portion of the 24% of batteries they don’t collect is composed of informal and non-compliant companies and is working with local governments to attempt to increase enforcement. This appears to be particularly a problem among retailers, due to the vast number of unconsolidated companies.

They further highlight some problems with the system, including unlicensed transporters and “adulterated batteries” that have water added to them to make them weigh more.

It does seem that the government has taken some action against informal companies, although it’s difficult to tell to what extent this has been successful. I couldn’t find details around enforcement against non-complying manufacturers/distributors/recyclers, but there seems to be a real effort to crack down on illegal scrap ULAB imports.

In 2020, IBAMA seized 16 tons of ULABs that were imported illegally from French Guiana to be sold to recyclers in Brazil and fined the company around $20,000 USD. In 2023, an auto parts company in Parana was convicted of illegally importing ULABs from Paraguay.

Recently, it seems the Brazilian Federal Police have scaled up efforts to apprehend ULAB smugglers, launching “Operation 12 Volts” this January to target illegal scrap ULAB imports from Uruguay.

Per the press release, “federal police officers are carrying out seven search and seizure warrants in the municipalities of Santana do Livramento/RS (2), Porto Alegre/RS (3) and São Paulo/SP (2) and are executing the Federal Court's order to block R$6 million in the suspects' bank accounts and to seize three properties, also valued at R$6 million.” (R$6mm is around $1.2mm USD, for a collective asset seizure from these raids of ~$2.5mm USD).

The existence of a coordinated, named, federal police operation to stop this kind of illegal ULAB imports seems great. But this kind of enforcement only makes sense if you have a good legal system that ULABs are otherwise being channeled into.

With IBER, it seems that Brazil has created that system.

Many thanks to Mikey Jarrell and Etienne Dyer for edits.

Kelly Polido Kaneshiro Olympio et al., “What Are the Blood Lead Levels of Children Living in Latin America and the Caribbean?,” Environment International 101 (April 2017): 46–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.12.022.

M. M. B. Paoliello and E. M. De Capitani, “Occupational and Environmental Human Lead Exposure in Brazil,” Environmental Research 103, no. 2 (February 1, 2007): 288–97, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2006.06.013.

Mariana Maleronka Ferron et al., “Environmental Lead Poisoning among Children in Porto Alegre State, Southern Brazil,” Revista de Saúde Pública 46 (April 2012): 226–33, https://doi.org/10.1590/S0034-89102012000200004.

2008: CONAMA Resolution No. 401

In 2008, CONAMA, Brazil's National Environment Council, passed CONAMA Resolution No. 401 (English version here). It was the first national policy specifically targeting ULABs, and outlined the form that later ULAB regulation would take.

It required:

Battery manufacturers and importers to register with the government as part of the Federal Technical Register of Potentially Polluting Activities (CTF), as well as submit submit management plans that outlined how they would ensure batteries were properly handled and ultimately disposed of.

A (loose) reverse logistics system for ULABs. All establishments that sold batteries were required to have collection points and accept used batteries. It was the responsibility of the battery’s manufacturer or importer to ensure batteries collected through this network were appropriately recycled.

To improve ULAB traceability, batteries needed to be labeled with their manufacturer and/or importer.

Batteries needed to be transported with their electrolyte solution. This may seem random, but the drainage of the (lead-contaminated) acid from ULABs to reduce their weight is a widespread problem in the informal sector.

IBAMA, the Brazilian Institute of Environment and Renewable Natural Resources, was put in charge of issuing instructions around how companies needed to comply with reverse logistics and ULAB recycling requirements.

Also 2008: Federal Decree No. 6.514

The CONAMA resolution went into effect alongside another piece of 2008 legislation, Federal Decree No. 6.514. This law defined penalties and enforcement powers for a wide range of environmental violations, not just those specific to lead-acid batteries.

The fines outlined were substantial, with maximum penalties as high as R$50 million (around $20 million USD at 2008 exchange rates). Environmental agencies were granted broad powers to enforce compliance, including the ability to seize products, embargo property, and suspend operating licenses.

2010: The National Solid Waste Policy (Law No. 12.305)

The National Solid Waste Policy (Law No. 12.305, English here) enacted in 2010 marked a major shift in Brazil's environmental regulations, with significant impacts on ULAB recycling. It mandated reverse logistics and “shared responsibility” (basically, EPR) for a wide range of products nationally, including lead-acid batteries.

This article is a great analysis of the stakeholders and what went into getting the law passed. It seems it was partially a consequence of growing state-level regulation, which prompted companies to support more unified federal legislation.

While the 2008 CONAMA Resolution had required that batteries be taken back, the PNRS mandated a more comprehensive reverse logistics system, stating:

“manufacturers, importers, distributors and sellers of the products below [including batteries] are compulsorily required to frame and implement reverse logistics systems upon receiving products from consumers.”

(2010 National Solid Waste Policy, Article 33)

The PNRS was explicit about how these reverse logistics systems would work.

Consumers were required to return waste to sellers or distributors. These sellers and distributors were then required to return the material to manufacturers or importers, who were ultimately responsible for the “final environmentally-adequate disposal of products and packaging collected or delivered.”

Environmental regulators were given the ability to define what met these “environmentally-adequate” standards.

2011: CONAMA Resolution No. 436

CONAMA Resolution No. 436 (English here) was published at the end of 2011 and targeted emissions from older secondary lead smelters — those with operating licenses issued before 2007. (The lead-specific details are in Annex VIII.)

It imposed restrictions on air lead emissions, and required that secondary emissions and air leakage be captured and filtered. It also called for the testing of air, solid, and surface water near smelters, with monitoring to be carried out on a schedule set by the environmental licensing body.

It’s not clear how large of an impact this had, but it represents a specific attempt to go back and improve emissions at previously licensed lead recyclers.

2012: INMETRO Ordinance No. 299/2012

On June 14th, 2012, INMETRO (Brazil’s National Institute of Metrology, Standardization and Industrial Quality) issued INMETRO Ordinance No. 299/2012. The ordinance established that all lead-acid batteries for vehicles sold in Brazil needed to be certified, and their manufacturers and importers needed to be registered with INMETRO.

In particular, they had to provide the battery weights — these could easily then be verified at retail locations to ensure that the battery being sold had a similar lead content and weren’t an attempt to sell lower quality batteries.

The INMETRO certification is carried out through a Product Certification Body (OCP), who is responsible for conducting audits and assessments to ensure supplier compliance. If you’re curious about how this process works, this is a detailed 2020 analysis of INMETRO’s battery regulation and how it affects Clarios, the world’s largest lead-acid battery manufacturer and a major player in the Brazilian market.

Sample INMETRO conformity identification seals, to be placed on all registered lead-acid batteries sold in Brazil. (Per INMETRO Ordinance No. 299/2012)

The INMETRO ordinance substantially expanded reporting requirements around ULAB recycling. Battery suppliers were required to submit not only their used battery management plans, but also specific details around it. This included up-to-date operating licenses for Brazilian factories from the relevant environmental agencies, and proof of good standing with the Federal Technical Register of Potentially Polluting Activities.

This reporting also followed the used batteries further down the supply chain, ensuring that the suppliers were using contractors and recyclers that were themselves compliant. Battery suppliers were required to submit proof from an environmental agency that the lead recycler they used was environmentally compliant.

As part of their annual activity report, battery suppliers were also required to submit quantitative reporting on their own sales and collection efforts. This included the quantity of batteries they sold or imported, the quantity of ULABs taken back, and the quantity of ULABs sent to the recycler. This was to be combined with a declaration from their recycler that they had indeed received that quantity of ULAB, and a signed contract between the supplier and the recycler regarding ULAB recycling. There were some additional requirements for declarations from contracted recyclers, including monthly breakdowns of batteries received from the supplier and a corresponding list of delivery invoices.

Under the National Solid Waste Policy, lead-acid battery suppliers were responsible for taking back and recycling ULABs. INMETRO Ordinance No. 299/2012 made this more enforceable, and began to require that in order to be able to sell or new import lead-acid batteries into Brazil, the suppliers must be able to regularly prove that the used batteries they were collecting were being formally recycled by licensed recyclers, with additional verification through the recycler’s own declarations.

Also 2012: IBAMA Instruction No. 8/2012

The next big piece of national ULAB regulation was IBAMA Normative Instruction No. 8/2012, issued a few months later in September 2012. Framed around the 2008 CONAMA Resolution, it set forth detailed reporting requirements for ULAB recycling in the Federal Technical Register of Potentially Polluting Activities (CTF), which IBAMA manages.

Here’s our somewhat poorly-formatted English version:

Like the INMETRO regulation, the IBAMA instruction was similarly interested in following the lead-acid batteries after their manufacture/import.

Lead-acid battery manufacturers and importers had already been required to register with CTF under Conama Res. No. 401. Now, however, battery recyclers and transporters were also required to register with CTF and file annual reports. As a result, effectively anyone who handled lead-acid batteries was required to be registered with the government.

The instruction laid out details about what each party should report. Manufacturers and importers, who had already been required to prepare battery management plans, were now required to submit them as part of their CTF Annual Activity Report. They also needed to report the quantity of batteries they had manufactured or imported that year, the quantity of ULABs they had collected, and the details, including names and addresses, of their ULAB collection points.

Manufacturers and importers further needed to report details on the transporters and recyclers they contracted with. Importantly, this includes the contractors’ CNPJ numbers — a unique number for every legal entity similar to an American EIN.

Recyclers needed to report the total volume of batteries they recycled, as well as the CNPJs of the companies that supplied them.

Combining these requirements, a relatively auditable system emerges. By tying all of the details around ULAB recycling and quantities to unique business identifiers, the CTF now had a relatively comprehensive picture of the formal ULAB recycling market and its flows.

The IBAMA instruction also made clear that if a company was contracted to import batteries but wasn’t actually selling them, the company that sold the batteries would be responsible for the CTF reporting requirements. To ensure this, it required that the importer submit to IBAMA a certified signed agreement between itself and the company it was importing the batteries for demonstrating the link between the imported batteries and the company with the CTF obligations. If an importer failed to do so, they would retain the reporting obligations.

2013: IBAMA Normative Instruction No. 1/2013

IBAMA Normative Instruction No. 1/2013, tied together parts of the National Registry of Hazardous Waste Operators (CNORP) with the CTF (both of which applied to lead-acid batteries).

2015: SMA Resolution No. 45/2015

In 2015, Sao Paulo’s Environmental Secretary passed Resolution No. 45/2015, which created reverse logistics requirements for products sold in the state that were potentially environmentally hazardous, including lead-acid batteries.

2016: São Paulo Term of Commitment for ULABs

On December 21st, 2016, a new term of commitment for lead-acid batteries went into effect.

It was signed between the Sao Paulo Ministry of the Environment, CETESB (the Environmental Agency of the State of São Paulo), ABRABAT (The Brazilian Association of Automotive and Industrial Batteries), FecomercioSP (Sao Paulo’s main industry group) and the newly-created IBER.

It explicitly laid out how the reverse logistics system would work. Dealers and distributors were to collect batteries from consumers, who would trade them in when they bought a new battery. These ULABs would then be periodically collected by the manufacturers/importers and then delivered to environmentally responsible formal recyclers.

It also set a specific set of ULAB collection targets for manufacturers and importers, scaling up from 75% to 90% of new batteries sold. To make it simpler and more accurate, the accounting for both new and used batteries was done by weight.

Translation of 2016 Sao Paulo Term of Commitment (page 12) setting ULAB collection targets in the region (Trans. DeepL)

Under this term of commitment, ABRABAT (the Brazilian battery industry group) would provide the initial financial support for IBER, support its implementation, and encourage its members to join. FecomercioSP would help promote reverse logistics across battery distributors and retailers.

2019 Sectoral Agreement

In August 2019, IBER, ABRABAT, and Sincopeças Brasil (a group representing auto parts distributors and retailers) entered a sectoral agreement at the national level with Brazil’s Ministry of the Environment.

Brazil’s national targets for ULAB collection (from the 2019 Sectoral Agreement)

The details of this agreement were similar to the previous state-level terms of commitment that we’ve looked at already. Perhaps most importantly, it expanded the kind of reverse-logistics systems we’d across the country, and created national and regional targets for ULAB collections. IBER would be responsible for managing this national system, and reporting information on the system and compliance to the Ministry of the Environment.

Although the 2019 sectoral agreement was a major step in making clear IBER’s national role in managing Brazil’s ULAB sector, through the state-by-state terms of commitment, IBER was already relatively large by the time the sectoral agreement was signed.

It represented the manufacturers of more than 75% of batteries sold on the Brazilian market, and through the terms of commitment across four major states — Sao Paulo, Parana, Rio Grande do Sul, and Minas Gerais — a large share of Brazil’s population and market as well.

Since the MMA, IBER has continued to sign and renew terms of commitment with states, coordinating their system with the states’ environmental authorities.

2023 Federal Decree No. 11.413/2023

In the beginning of 2023, the Brazilian government issued Federal Decree No. 11.413/2023. This scaled up some of the requirements around reverse logistics at a national level stemming from the 2010 PNRS.

It outlined details around how management entities like IBER could certify that member companies were in compliance with reverse logistics requirements. As before, companies could rely on membership entities, or prove that their individual systems were effective directly to the Ministry of the Environment.

It further mandated that management entities as well as individual companies use independent results verifiers, themselves registered with the government, to verify that their data and certifications are accurate.

Finally, it required at a national level that all companies comply at a level equivalent to the reverse logistics targets that management entities did — this cemented management entities at the core of Brazil’s national ULAB policy, and meant that you could either join IBER, or prove you had met the same targets alone.

Early Sao Pãulo regulation

In SP, the first term of commitment for lead-acid batteries was signed at the end of 2011, and CETESB, the Environmental Agency of the State of São Paulo, was put in charge of ensuring compliance.

Manufacturers had some additional reporting obligations to the state, but largely the 2011 ToC was similar to pre-existing CONAMA and PNRS requirements.

In 2015, Sao Paulo’s Ministry of the Environment also passed Resolution No. 45/2015, which created reverse logistics requirements for products sold in the state that were potentially environmentally hazardous, including lead-acid batteries.

Under this resolution, affected companies had to prove to CETESB that they were compliant with reverse logistics requirements in order to receive or renew an operating license, without which they couldn’t do business.

There were two ways companies could prove they were compliant with regulations. They could enter a term of commitment with the state environmental agency, in which case compliance would be as defined in the agreement, or they would be required to prove to CETESB directly that they were compliant with the regulations and met targets equivalent to those outlined in terms of commitment.

In June 2016, CETESB issued Decision No. 120/2016/C. This exempted companies that were adherents to terms of commitment from certain environmental licensing requirements, which further encouraged companies to enter terms of commitment.

The Brazilian battery industry would do exactly that, entering a term of commitment with the Sao Paulo government on December 21st, 2016 and creating IBER in the process.

In 2017, IBER, ABRABAT, and FecomercioPR signed a term of commitment with the State of Parana. It seems to be very similar to the Sao Paulo ToC, and it established the same scaling set of collection targets.

The same year, the national Guiding Committee for the Implementation of Reverse Logistics issued Resolution No. 11/2017, which emphasized the role of management entities in reverse logistics at a national level. Federal Decree No. 9.177, also 2017, encouraged the structuring of sectoral agreements for reverse logistics at a national level.

In 2018, IBER, ABRABAT, and FecomercioRS entered into a term of commitment with the State of Rio Grande do Sul. It had the same scaling targets of the previous two terms of commitment, and was broadly similar, although it had some more explicit details around how IBER implementation would work, including annual audits and privacy protections.

It also discussed IBER’s online platform in detail, providing some insight into how companies actually used IBER.

In April 2019, IBER and ABRABAT entered a term of commitment with the state of Minas Gerais. It seems to be basically the usual, but interestingly, it had a section on “large consumers” — those who purchased more than 20 tons of batteries a year — requiring them to make their ULABs available for collection and encouraging them to join IBER. It also had slightly more aggressive targets, with a year one target of 80% versus the others’ 75%.

This comes from an excellent 2018 analysis of IBER’s early days. Coelho is more broadly interested in managing entities for reverse logistics, but lots of good IBER details:

Arnolfo Menezes Coelho, “Sistemas de logística reversa pós-consumo: um estudo comparativo entre os setores de baterias chumbo-ácido, embalagem de óleo lubrificante e pneus,” June 29, 2018, https://hdl.handle.net/10438/24507.

IBER annual reports

Couldn’t find a centralized source for these but was able to find them in random places online.

Each contains details on somewhat different projects and goals they were working on, so if you’re interested in the specifics of how IBER works, they’re probably all worth a read.